Description

Plains zebra (Equus quagga), also known as the common zebra, is the most common species of zebra. It can reach up to 1.1-1.4 m (3.6-4.8 ft) at its shoulder and a length of 2-2.5 m (6.6-8.2 ft). Weights reach 175-385 kg (386-840 lb), with males often being 10 % heavier than females. It is one of three zebra species, with the other two being the mountain zebra (Equus zebra) and the endangered Grevy’s zebra (Equus grevyi). Zebras are thick bodied with short legs and have a characteristic coat of black and white stripes. The three species are distinctly different in their pattern, and the plains zebra itself has several subspecies which can be differentiated by coat pattern. The plains zebra is distinguished from the other two species by having black stripes going down and across its belly, whereas the other two have stripes that are cut short before an all-white belly. The Grevy’s zebra is probably the easiest to distinguish, as it has markedly narrower stripes than the other two.

Diet & habitat

Plain zebras are primarily grazers, with around 90 % of their diet being grass. They can, however, eat a great variety of vegetation and do sometimes even browse leaves from bushes and low branches. This is one of the reasons it is such a common and widespread species.

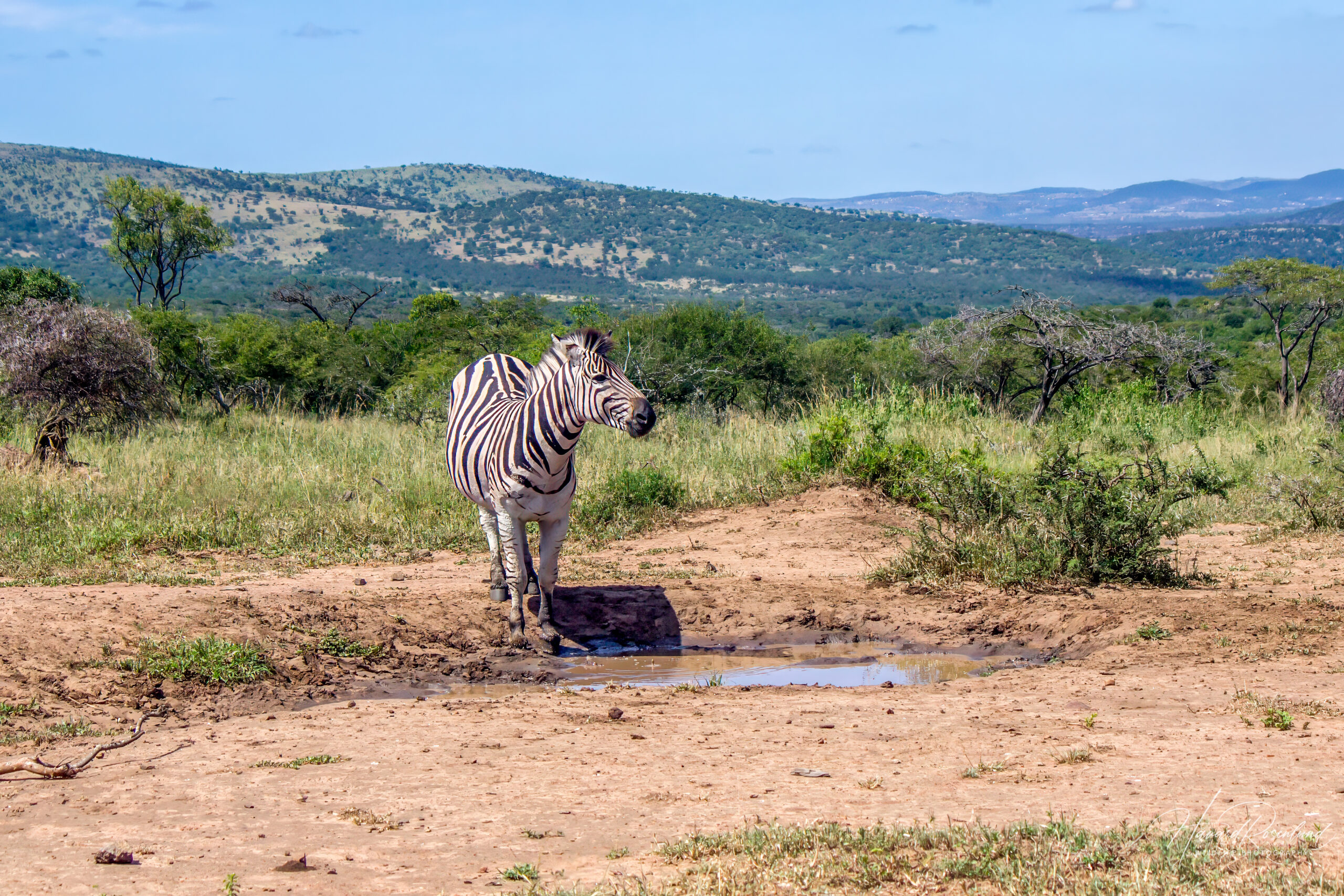

Plains zebra is normally found in open grasslands and savanna woodlands, and rarely ventures into forest habitats. They are water dependent and are normally found within 25-30 km away from water sources, and thus they shy away from desert habitats. Plains zebras are known to migrate long distances for both food and water. One population of a few thousands individuals migrate over 500 km (300 miles) across Botswana and Namibia, making it the longest mammal migration on the African continent. Every year several hundred thousand plains zebras also join the 1.3 million wildebeest in the great migration in the Serengeti ecosystem, where they follow the rains and fresh grass.

Social behavior

Zebras are highly social animals and live most of their lives in harems. A harem consists of one male, a stallion, and all his females, called mares, as well as foals and subadults. Young stallions leave their natal group to join bachelor groups, and the oldest male will normally be the leader of such a group. Though oldest, the leader of a bachelor group is seldom an old individual, as they normally stay in such groups until they are old enough to create their own harems. Once a stallion has procured his own harem, he will be very protective of it and will normally not allow any other males near his mares. However, harems do often come together to form larger herds, and mares from different harems will then interact.

When creating his own harem, a young stallion will try to steal mares from another harem. The mare stolen will often be young and fertile, and the young stallion and the harem leader will often fight over her, even though the young mare is often a daughter of the harem leader. Fighting between stallions can often be quite violent, with a lot of biting and kicking. After a stallion has successfully abducted a mare he will have to keep fighting other bachelors off. This will be ongoing until her estrous cycle is over. The stallion that eventually impregnates the mare will keep her in his harem. Harems can also be taken over by young bachelors if the leader is old or weak. Healthy stallions most often keep their harems.

Reproduction

A stallion will normally mate with all his mares, and mares might give birth every 12 months. Due to conditions being more favorable, births occur most often in the rainy season. A stallion does not tolerate foals not sired by him, and he might commit infanticide if he comes across one in his harem. After birth the foal does not take long before it can fully walk and even run. The mother will keep the rest of the harem away from the foal in the very beginning. The stallion and the other mares will protect any foals within their harem from harm. Here’s a video of a 20-minute old foal taking its first steps. Notice how the mother is keeping the others in the harem away.

Why stripes?

A common question asked when it comes to zebras is: What functions do the stripes have?

There are still no certain answers to this, but plenty of good theories have emerged. Some postulate the stripes are there as camouflage to hide the zebras in tall grass, shade and so forth. Evidence seems to go against this idea because of the zebra’s tendency to be loud and present in its behavior. An idea likely to be closer to the truth is a theory that the zebras have stripes to confuse predators, by making it harder for a predator to single out or focus on one individual as the zebras move, especially when in groups.

Another likely hypothesis is that the pattern has evolved for social reasons, as evidence suggest that zebras can tell each other apart. The stripes will help family members and harems stick together when moving and running from predators.

There is a third theory that zebras have stripes to avoid bites from the bloodsucking and disease-bearing tsetse fly, as zebras are more susceptible to these diseases compared to other wild African mammals. The tsetse fly needs the animal to be plain colored to successfully detect its target, and, because zebras are striped, they do actually get fewer bites than other animals.

One cannot say for certain why the zebra has stripes, but it might be one, a couple, or all of the above.

Predation

Zebras are quite successful at escaping predators, and the stripes could be one reason for it, as is explained above. Lions seem to prefer zebra over many other prey species, but rarely succeed at catching one. This is why you often see zebras with big scars on their backside from failed lion attacks. Catching zebras poses a great risk to any predator, as a kick to the head can be lethal. If a zebra manages to get some good kicks in on a potential attacker, the hunter might think twice before continuing the chase.

Status

The plains zebra is common throughout most of its now reduced range in East and Southern Africa, especially in protected areas. It is divided into six different subspecies, with no immediate threat any of these. The species is experiencing a reduction in numbers, however, and especially northern populations has seen a decline due to civil unrest and conflicts. In heavy war-thorn areas, populations have gone extinct. The main threats are poaching in the northern parts of its range and habitat loss in the southern. It is listed as near threatened on the IUCN Red List.

Quagga

The extinct quagga (E. q. quagga) was originally thought to be a different species, as it only has stripes on the front part of its body, with the rest of the coat being a dark brown. Recent genetic studies have shown the quagga to be a subspecies of the plains zebra. It was also the very first described zebra species, which is why, due to rules in taxonomy and the recent genetic findings, the Latin name for plains zebra changed to quagga from burchellii. Because of the close genetic relationship there is now an ongoing breeding program to try to breed the quagga back to life using plain zebras with similar physical traits. The last quagga died in the wild in 1878 due to over hunting by the South African Dutch settlers, and the last captive animal died in Amsterdam on August 12th, 1883.